Tracing Yan’an caves where Japanese captives became anti-fascist warriors

Xinhua2025-08-28 17:13

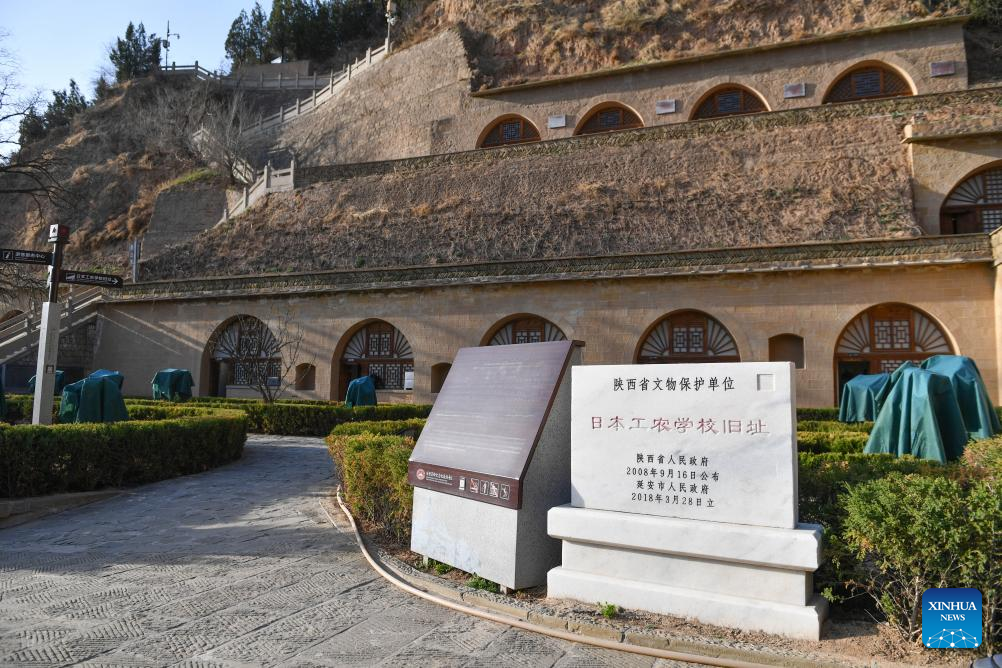

This photo taken on March 23, 2021 shows the site of the Yan'an Japanese worker and peasant school in Yan'an, northwest China's Shaanxi Province. (Xinhua/Zhang Bowen)

YAN'AN, Shaanxi Province, Aug. 27 (Xinhua) -- As a child, Yokichi Kobayashi devoured Chinese novels about the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and puzzled over why some Japanese captives later aided the Chinese, only to discover the answer in his father's own story.

Over the past 50 years, he meticulously pieced together the life of his father, Kiyoshi Kobayashi, eventually chronicling it in a biography. This year, which marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the War of Resistance, the 74-year-old Japanese authorized a Chinese website to publish the book.

"As a Japanese, I ultimately chose to fight alongside the Chinese during the War of Resistance because the Communist Party of China (CPC) helped me realize the injustice of Japan's war of invasion," Kiyoshi once told his son.

The Yan'an Japanese worker and peasant school re-educated many Japanese captives, changing their perspectives, said Yokichi. "Many of them later joined the fight against Japanese fascism and became a crucial force in the World Anti-Fascist War, helping to accelerate the path to victory."

THE SCHOOL THAT CHANGED THEIR LIVES

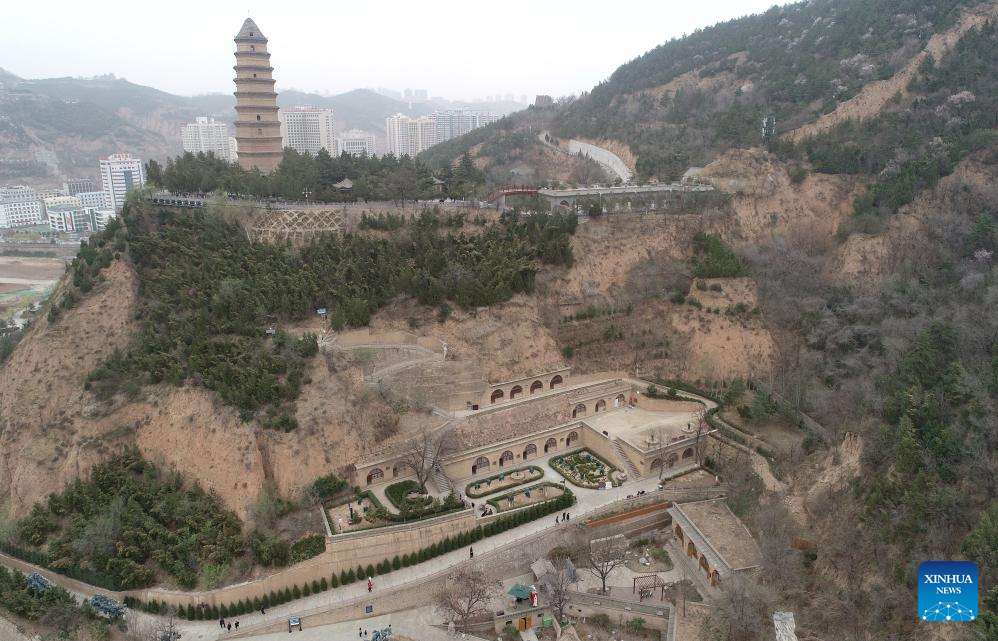

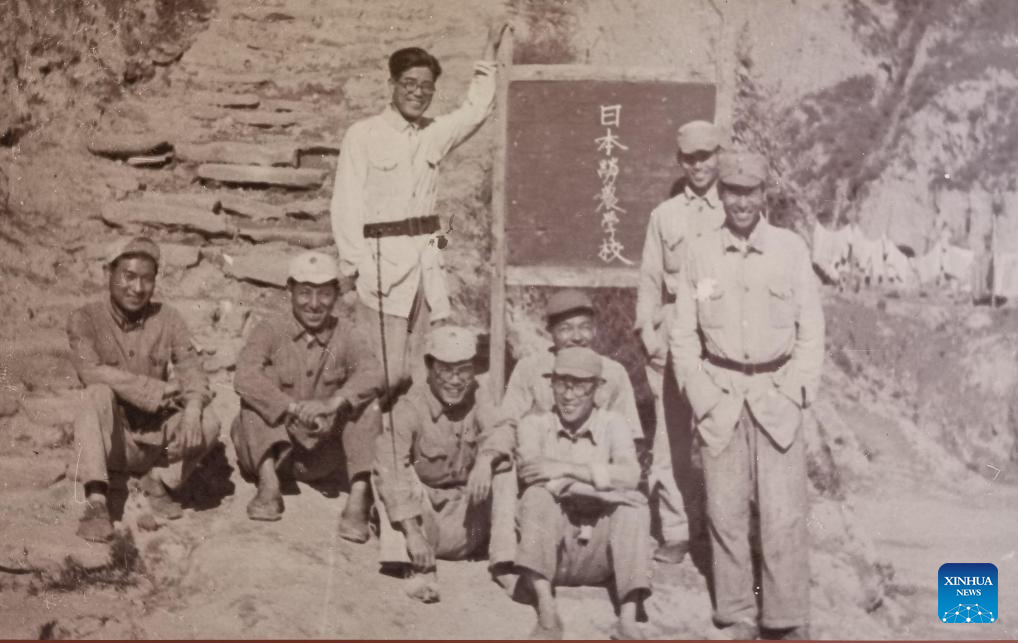

The school officially opened in May 1941 on the towering Baota Mountain with just 11 students, and by August 1945, before the end of the war, enrollment had grown to over 300. More than 30 cave dwellings served as dormitories, classrooms and other facilities.

Today, some of the well-preserved caves draw visitors from across China.

"The school, primarily enrolling Japanese prisoners of war, aimed to transform their mindset. It reflects the effectiveness of the Party's efforts in disintegrating enemy forces during the War of Resistance and demonstrates the significance of the Party's military-political work," explained Li Donglang, a professor with the Party School of the CPC Central Committee (National Academy of Governance).

Kiyoshi was born into a businessman's family in Osaka. In 1938, at the age of 20, he was enlisted and was sent to China the following year. In 1940, he was wounded in a battle against the Eighth Route Army and captured.

"At first, my dad tried to escape and even considered killing the Chinese army leaders," Yokichi said. "He even helped another Japanese prisoner attempt to flee."

Back then, Kiyoshi, like many Japanese soldiers, had been told that Japan's actions were "self-defense" and that their aggression was carried out "for the peace of the East and to punish China."

During his study in Yan'an, he gradually came to realize that neither the Chinese nor the Japanese people wanted the war, which had brought massive suffering to both countries. He himself was a victim, forced to leave his happy family at a young age. Moreover, the Japanese warmongers had clearly underestimated the strength and determination of China.

At the site of the school, display boards recount this little-known history to visitors.

Information on a display board shows that the students led a regular daily life, with morning exercises, classes and discussions. Their courses covered politics and economics, Japanese affairs, current events, philosophy, world geography, Chinese language and even art.

Kiyoshi told his son that what he had learned in Japan was merely propaganda. "Only through his own study did he truly grasp the concept of class and recognize the exploitative and aggressive nature of the reactionary class," Yokichi said.

Data show that 53.8 percent of the students were workers, while the rest were farmers, shop assistants, businesspeople, and others. Most had been ordinary soldiers or low-ranking officers when captured.

In revolutionary bases like Yan'an, prisoners of war were treated well, a stark contrast to the practices of the German fascists and Japanese militarists during the war.

A 1943 menu shows that students had meat every day. Thanks to the self-sufficiency campaign known as the Great Production, people in Yan'an enjoyed adequate food and clothing.

In the biography Yokichi documented, he recalled his father making dumplings with fellow students. "When the dough and filling were brought from the kitchen, everyone scrambled to make them, often breaking the wrappers or overstuffing them," he wrote. "With the help of Chinese comrades, it took some time, but my father gradually learned the skill."

At that time in Yan'an, the students lived vibrant lives. In their spare time, they made their own chess, mahjong and baseball equipment. Black-and-white photos on display show them taking part in various performances, during which Japanese students danced alongside Chinese soldiers.

After graduation, many of the former Japanese soldiers took part in various anti-war activities. Some voluntarily joined the Eighth Route Army and went to the frontlines, playing a significant role in weakening the morale of enemy forces.

A BOND CONNECTING TWO COUNTRIES

In 1945, after Japan surrendered, Kiyoshi was tasked with persuading some Japanese soldiers to lay down their arms. After the negotiation, the soldiers were convinced and asked him, "Are you Japanese yourself?" "Yes, I am," Kiyoshi replied. "But I am now a member of the Eighth Route Army."

After the war, as he decided to stay in China, most of the students went back to Japan. But many revisited the caves in the following decades.

Takashi Kagawa and five other Japanese returned to the site in 1979. "I have always regarded Yan'an as my second hometown. In my youth, I gained a new worldview and outlook on life there... Hundreds of Japanese youths came to recognize the evil of aggression and joined hands with Chinese friends to end the war as quickly as possible. Many of them even sacrificed their lives in anti-war activities," he said.

Data show that nearly 50 members of the Japanese anti-war alliance lost their lives fighting against Japanese troops.

"The United Front was one of the key tools the CPC used to defeat the enemy during the war," said Hao Xueting, former research office director of the Taihang Memorial Museum of the Eighth Route Army.

The caves underwent preservation over the following decades. Some were damaged by heavy rains in 2013. Renovation started in 2015 before the caves opened to the public four years later.

Yokichi said he hopes to visit the place where his father lived and studied one day. He is now the head of a Japanese organization dedicated to fostering friendly relations between Japan and China.

"I feel obliged to carry on my father's wish to cherish peace and oppose war, to help more people understand that the friendship between Japan and China was hard-won, and to ensure that the clock of history never turns backward," Yokichi said.

He went on to add that today, more than ever, Japan needs to learn from its past. "A country's self-reflection is more important than another's tolerance," he said. "Only a country that dares to confront its mistakes can truly earn the respect of the world."■

This photo taken on March 23, 2021 shows the site of the Yan'an Japanese worker and peasant school in Yan'an, northwest China's Shaanxi Province. (Xinhua/Zhang Bowen)

A drone photo taken on March 30, 2021 shows the site of the Yan'an Japanese worker and peasant school in Yan'an, northwest China's Shaanxi Province. (Xinhua/Zhang Bowen)

This file photo taken in September, 1945 shows some of the teachers and students of the Yan'an Japanese worker and peasant school in Yan'an, northwest China's Shaanxi Province. (Xinhua)